History is made at night

Character is what you are in the dark

Doesn’t matter, saw stars

Finally. Holy Toledo. I can’t flippin’ believe I finally got out in a dark field to see some stuff. The persistence of cloudy, wet weather has been a real pain and fairly discouraging, but yesterday, two days after it was originally predicted to change for the better, the skies cleared.

Went out to my Worcester observing site, which I still have to stay quiet about for the time being, a bit later than originally planned. After being caught in a few sun showers during the day and assessing the conditions to be such that I’d be sacked by the dew before I was even done setting up, I thought I was staying in for the night. Maybe I misread it, but I swear I saw the humidity and dew point drop sharply from 7pm to 9pm. I’m glad I re-checked!

I didn’t make it to the site until about 11pm, which was fine since the moon was still bright and above the tree line. It gave me a lot of light for setting up and once I was situated I just had a look at jupiter for a while until it set. Seeing on the horizon sucked, like it generally does, but once things were high in the sky, they looked pretty good.

I couldn’t wait for Mars to come up, so I’ll have to go back for it in the coming months. I’ve been looking forward to observing that little red SOB for some time now.

Since I always put some kind of pic or video on my posts, here’s one that doesn’t have much to do with anything.

Musical observation

Somewhere along the way, I read an article about music that you should definitely listen to while you’re out observing. It reminded me of another article from a UK newspaper listing the top-10 most dangerous songs to have playing in your car while driving. I think Grieg made both lists.

Anyway, my reaction to these lists was perhaps a sign of my experience with musical bias; I thought they were both totally ridiculous. As a former professional DJ, I know a thing or two about any collection of music appealing to various groups of people in different situations. This understanding is why I only performed at three weddings, ever, and only for people I knew personally. It’s damn near impossible to make a list of songs and claim that they’re going to have the same effect on anyone besides the list-maker with any consistency. Making suggestions is one thing, but saying anything qualitative about these kinds of compilations is silly, more so as they try to be very general.

When I was a wee lad, I talked my mom into calling an 800 number I saw on TV and ordering me a 3CD set of music called Cosmic Dreams, which is essentially an unofficial soundtrack for Cosmos. These CDs are somewhere in my basement, in storage, but lately I was thinking how cool it would be to listen to this stuff while on site. Of course, this is a collection of insanely cheesy new-age stuff and if I tried to make my wife listen to it, she’d either run for the hills or shove an eyepiece up my nose.

Astronomer or not, there is virtually never any opportunity available for you to impose your musical tastes on others while not also being an annoying jerk. Even making lists is fine, so long as you remember you’re representing your own taste. Suggestions work best when your audience has an awkwardness-free way to not listen to them. I’m not trying to say suggestions are bad, really, simply don’t confuse them with making people hear examples or acting as though you know what people are going to like. Radio DJs can have the frequency changed on them and DJs in clubs can have their audience clear the dancefloor, either way it’s not personal. Wedding DJs, on the other hand, have drunk (and sometimes irate) relatives of the marrying couple tell them to “Stop playing this club crap and start playing some smooth jazz! FOR THE LADIES!” That last one feels a bit personal.

The point is: you should listen to whatever you want, if you even want to listen to anything at all. There’s something to be said for silence, but perhaps more to be said for headphones.

M54 where are you?

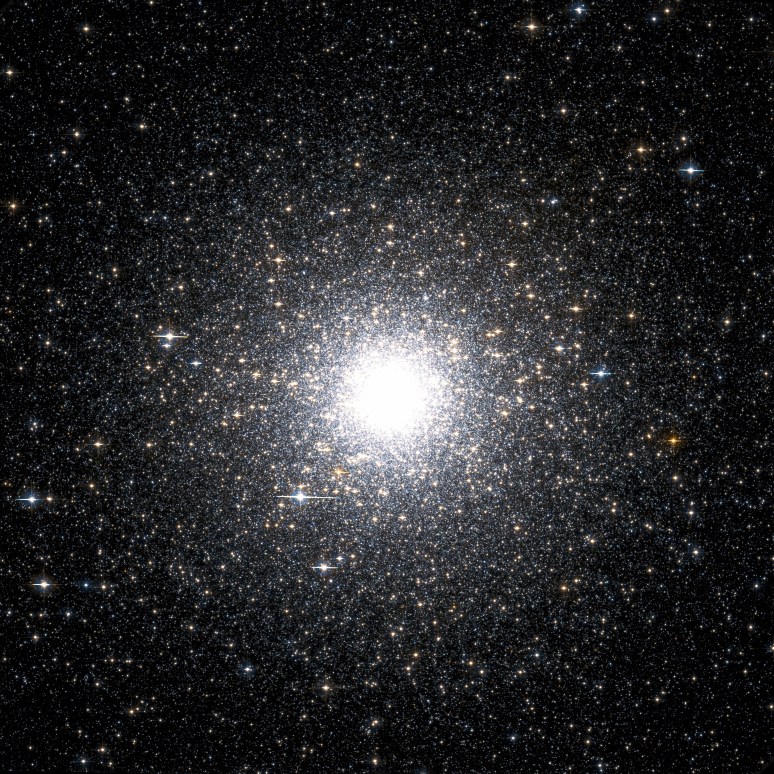

I’m a total goodie-two-shoes when it comes to not taking credit for stuff when I shouldn’t. For example: I read on Phil Plait’s Bad Astronomy blog about M53, a globular cluster that’s (sort of) recycling its stars, and now I’m posting about GCs. In order for the pun (which is obscure, don’t worry about it if you don’t get it) in the title to work, I had to mention M54, which is also a GC. It’s all so terribly convenient.

GCs are truly amazing, and breath-takers of the night sky. Sort of like mini-galaxies that orbit the Milky Way, their stars are much more densely packed and things get pretty rowdy in there. Stars even collide and consume one another, which is not something we commonly see, even when galaxies merge. I’ve always wondered what it would be like inside one, looking out. I imagine it would be a sky full of suns, light from every direction, but of varying color and it would be pretty darn easy to get a tan. I say we send Snooki into the heart of one immediately, she’ll love it.

By all means read the BA post about the cool stuff going on, but for simplicity’s sake, here are some amazing Hubble photos which will link to more info.

M54 appears to be in Sagittarius, but is not even in our galaxy, just close. My title gets more clever by the second!

M53 is the one Phil wrote about and looks a little different, but like M54, still reminds me of the 2001’s end sequence.

Remember, you can just look up into a dark sky and see these things. With binoculars or a small scope, they’re really something.

Interesting new product Monday: The $1000 eyepiece

Televue and Takahashi made names for themselves for making high quality, high price astronomical tools and accessories. Their eyepieces would make you think all anyone cares about is maximum FOV (field of view), which spending the maximum money will get you. I’ll just say now that I do not own eyepieces from either maker, but I do own other things made by Televue and I have a small amount of fist hand experience. Either way, this is not meant to be a detailed review of any particular item’s performance, but just a moment of reflection on some telescope accessories that cost more than a lot of telescopes.

First, let’s look at Televue ETHOS eyepieces. They offer FOV of 100 degrees, which is about what a human can see normally. They list from $730-$1050 each and you can expect to pay about $520-$730, depending on what size and format (1.25″ or 2″) you want. If you want to step it up to 110 degrees at high magnification, you can go for the ETHOS-SX, which is a bit more expensive than the others, but has an adapter for both formats. They’re huge too, but they need to be since they use many elements to achieve a wide FOV and non-distorted image. Customer reviews are great, but do you really expect anyone to drop that kind of coin on these and then say it’s no good? A ridiculously thorough and more objective review can be found here.

Next is the Takahashi Ultra Wide/Flat Field 1.25″ eyepiece. This comes in one format and offers a 90 degree FOV, all for the bargain price of $945. When I fist saw these, I thought that price was for the set, but no, that’s each. This is an 8 element, 5 group design, which means there are 8 lenses in each piece, carefully placed together (groups) and apart to achieve the claimed high optical performance. I wanted to link a good review for these online, but I can’t seem to find one. Do I even really need one though? These might be the finest 8 pieces of glass you’ll ever look through, but is that really why someone buys them?

There are many schools of thought for anything. If a very wide FOV that looks good to the edge of the field is important and money isn’t an issue, sure why not get the best thing you can? Questar knows there’s a market for stuff that’s simply the most expensive. Yes, they’re all nice and built very well, but at some point the price vs. performance ratio starts to matter. It’s up to the individual to decide how important the advantages a top-price piece of equipment is worth and if it makes sense for you, then I suppose it’s the right thing. For someone getting into the hobby, it can seem discouraging to see that the price scale is so huge, when it’s our common inclination to think that cost always correlates with quality. The price scale of telescopes is the same way, but it’s easier, I think, to understand those differences.

My personal approach is to try and get the nicest stuff I can for the least amount possible, which is not the same as buying the cheapest things. If I get internal reflections in an eyepiece, I’ll never use it. The inexpensive, but by no means “bad”, eyepieces that came with my telescopes have all been sold and replaced with slightly more premium ones. My current favorites are the Astro-Tec Paradigm Dual ED series. Sure they only have a 60 degree FOV, but they’re very comfortable, have excellent contrast and are enjoyable to use. I also like the Explore Scientific 82 degree waterproof series. They’re hefty, offer a very wide FOV and were on sale for $99, which I still think is a lot for an eyepiece, but they are also very nice to use. With so much glass, you lose a little contrast, so I also like an Abbe Ortho, which good quality ones can be had from University Optics. The eye relief sucks, the FOV is not more than 47 degrees and they don’t look like much. Looking at Jupiter with the amount of detail they provide is really amazing, however.

In the end, you need to get what you like. Knowing what you like before you get it is important, but not always possible. This is why going where you can have experiences with these things before dropping your hard earned duggits on them is an excellent use of your time. Expos like NEAF, star parties and (if you have one) a local shop are ideal choices. There’s only so much you can do online, but if that’s all you’ve got, it’s worth reading what you can.

This is part of the NEAF vendor area. You'll never find so much astronomy stuff in the same room anywhere else.

No matter what you wind up with, just remember it’s always going to be a gazillion times nicer than anything the founding fathers of astronomy used and they changed the world.

Sun of a…

I think we all have heard things about the lifespan and eventual “death” of our sun. When I asked about it as a kid, it was given an ambiguous “about five billion years” answer and some stuff about it turning red, swelling up and cooking us. There’s a bit more to it than that.

First things first. Our sun has already had a pretty interesting run over the last 4.6 billion years. After forming from its parent cloud of gas and dust, recycling the cast-off from a star who’s life had ended, it began to shine, but not quite as brightly as it does now. The over-simplified point to remember is that the sun’s dimensions are the balance between gravity crushing a lot of hydrogen together and those crushed hydrogen atoms being smashed together and releasing an EXTREME amount of energy as they’re forcefully converted to helium. Every second, 4 million tons of solar mass are lost to these reactions, some of which we get in the form of light, heat and solar wind.

Throughout the time that the earth cooled and things began to get cozy for the possibility of life, the light and heat from the sun gradually increased. Interestingly, even though the sun was less radiant in the past, the temperature of earth’s surface wasn’t any cooler, since we used to have a LOT more CO2 (carbon dioxide) keeping the heat we received local. The first life was all about this early atmosphere.

Then, as time went by, cyanobacteria and eventually plants came around, used up the CO2 and replaced it with O2 (oxygen). This took a while and the sun warmed up a bit. Things worked out.

Of course, the sun’s output is not steady and there are many cycles it goes through that vary the amount of radiance we get out here. I’ll leave the details of this alone for now, but it’s worth understanding how these effect us and our climate. I’ll add that over the eons and millennia, things go up and down predictably, so we know what happened and like a cheesy horror movie, we know what’s around the corner.

In 1.1 billion years the sun will be 10% hotter than is is now. That means our surface water evaporates, the moisture exacerbates the greenhouse effect and our earth’s water begins to be lost into space. Maybe we’ll be able to do something by then, maybe we’ll be gone. The sun will do as it will do, regardless.

In 3.5 billion years the sun will be 40% brighter and make sure no water remains on the surface of earth at all, it’s all leaked out into space. We’ll be something like a dry-hot venus. If anything still manages to be alive, it’ll be underground.

The real fun starts in 6 billion years. That’s when the sun uses up the last of its hydrogen and things start to get CRAZY.

This is when it gets bigger. The sun will swell to extend beyond the orbits of mercury and venus, possibly even us. This is when it becomes what’s called a red giant. Either way, we three inner terrestrial planets are TOAST. While our solar system is enjoying a period with only five planets, the sun will be burning its helium. This only buys it 100 million years and the end of the helium era is a violent time. The sun begins to pulse, blowing off its mass into space.

While the helium was being used, a core formed of oxygen and carbon about the size of earth. This thing is white hot, denser than anything you’ll ever hold and the true beginning of the end. This is all that’s left of our sun, a white dwarf. The size of it is still puffed up slightly from the intense heat that keeps it glowing, but even as it gradually cools and shrinks, there isn’t far for it to go.

After trillions of years, yes TRILLIONS, it will cool into an object that is as cold as the space around it. We call this a black dwarf. We’ve never seen one, aside from the fact that detecting one would be almost impossible from any average stellar distance, because the universe isn’t even close to old enough for one to exist. Still, we know where one will eventually be, long from now, long after us, every morning when we see the sun rise.

I’ll let Dr. Sagan have the last word for this one.

Insane in the brane

I mentioned earlier this week that there are a LOT of galaxies out there. They get together in groups, which form into super clusters, which spread out like a fractal webwork throughout the observable universe. If this were a cosmology blog, I’d follow that opener with a gargantuan post about how we think these structures form and why there are VAST bubbles of empty space between them. For both our sakes, I’m going to skip that part and keep things in the realm of the 3D. Otherwise I’d have to get into non-observable additional spacial dimensions and dark matter, along with dark energy. Of course, thanks to some newsworthy neutrinos and some seemingly careful experiments, the observable (or measurable) dimensions of space we can count might soon be four.

This is a recent computer simulation of the large scale structure of the universe. I’m re-blogging this bit from Universe Today, which I think you should be reading as well anyway.

Pretty nifty! By all means read the UT post for a good explanation of what you just saw. But what about the real thing? After all, the simulation is cool, but it’s only a simulation. Of course, maybe we’re all just part of a MORE elaborate simulation. Let’s just say for now that what we think is real is real and do our best to avoid slipping down any rabbit holes.

When it comes to actually mapping everything all out, the project that got it done was the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. There’s a good book about how it all came together too. These guys have been mapping the universe since the 90s and the data may look familiar.

Looks just like the simulation!

How amazing is it that we can not only measure the structure of the universe, but actually make sense of it all? If this is interesting to you, check out the Sloan site and also some free info from NASA about how a lot of this stuff works. Some people might be surprised to learn that there is more to this stuff than just a bunch of tweed-jacketed academics scribbling complex equations on a blackboard. This isn’t all just conceptual, despite the incomprehensible scale. There is much more to learn, of course, and we still find ourselves only at the very beginning of truly understanding our universe, much less our place in it.

I was reading recently about a scientist that was boldly complaining that we had learned all there was to learn, the only mysteries in the universe were nagging bits of trivial minutia. This was about 200 years ago and I don’t remember his name. I heard someone recently saying something similar, but I’m probably not going to remember them either. Will anyone?

UFOs: Spacious accommodations

WooT! Time for another Unqualified Friday Opinion!

As I mentioned in my post yesterday, life as we know it has an expiration date. When that will be exactly depends on both us and our legacy, but at some point in the future, something will have to give. The most sensible thing, should we consider reproducing at the rate we are, will be to find accommodations elsewhere. Perhaps this is on the moon, Mars or simply in space. Some of the challenges we are aware of, a few of them we can currently address, but most I think are still going to need centuries of work to figure out.

Earth is a pretty safe place for we fleshy things that dwell upon it. We have a country club-like atmosphere we can breathe and that shields us from virtually everything that wants to recklessly slam into us and ruin our day. The temperature is well suited to having liquid water around, which we’re mostly made of, so that’s good. We have a magnetic field protecting us from a lot of the bad stuff that would fry us or turn our chromosomes to soup, plus gives us some free entertainment. All in all, it’s great. It’s also currently our only option

If there’s one thing humans can’t stand, it’s not having options. When earth starts getting more crowded, we’re going to feel some urgency to have a “plan B”. Since living at the earth’s core is impractical, we’re going to want to check out our options out in the final frontier.

Sounds exciting! My relatives will be flying all over space like Captain Picard and solving problems on alien worlds in 44 minute segments! How cool!

Well, depending on how our technology moves forward, we may or may not be warping all over the galaxy. 50 years ago, everyone was pretty sure we’d have flying cars by now, and we know how that turned out. There are a few things that currently stand in the way of our interstellar habitation, most are pretty nasty too.

Cosmic rays are a huge bummer. Way out in the distant reaches of everywhere, stars are exploding and hurling radiation at us at close to the speed of light. Some of this radiation is very dangerous and once you leave Earth, you leave the safety of its embrace. Astronauts that have left the Earth’s magnetosphere experience streaks flashing through their eyes. This is cosmic radiation causing brain damage. Lame! It’s estimated that if you hung out on magnetic field free Mars for two years, you’d lose 40% of your brain to cosmic ray damage.

“Yeah man, but we’ll just put up our deflector shields and be fine while we lounge around and drink sythohol in Ten Forward.” OK, let’s say we figure out deflector shields and can protect ourselves, I suppose we’ll HAVE to get past that hurdle anyway. Let’s consider how we’re going to take care of ourselves otherwise. If we live on a space station, or even on the moon or Mars, we’ll have to power our stuff, grow our food and have some way to manage a mode of habitation that is truly alien to us. Just the psychological strain of living on a small moon base might be more than most people could handle. Sure, the view might be nice, but it’s not like you can easily go for a walk.

Plus, we have evolved to live on the largest hunk of rock in the solar system and once we spend enough time on a smaller body with lower gravity, we might not ever be able to return to Earth. We’re built to Earth specs and those are hard to replicate. Mars, for example, has 38% of Earth’s gravity. So, if you weigh 200lbs on earth, you weigh 76lbs on Mars. This might make for some exciting basketball in the martian future, but this also means an earthling’s body would adjust dramatically to these new conditions. These adjustments include your body altering the amount of blood in your veins and your heart losing mass. Living on the moon or in a zero/micro gravity environment would only exacerbate this.

For the sake of this post’s readability, I’m going to skip right over the whole terraforming issue and save that for another time.

While the future is unknown, it is there. We have no idea what will come. We’re working on these issues now though, in some ingenious ways. The prospect of colonizing new parts of space is something I think comes as a very natural idea, despite all the hurdles we have to face. Maybe someday, not in the coming centuries, but the coming millennia, we will find a way to leave the glow of our home star and find a home on a planet much like Earth. Science fiction is rotten with stories about worlds that are habitable and already have life, while today’s exoplanet surveys bring the discovery of such a place closer every day. Fortunately for any one we find, its distance will keep it from us for a long, long time.

Carl Sagan once said that if we do find life on another world, we should leave it alone, even if it is nothing more than a bacterium. How would you like it if some aliens had decided to move here 200 million years ago and set up a theme park with dinosaurs? We might never have happened. Interference is nearly impossible to avoid and we should be mindful of this. The good news is we’re going to have a LONG time to think about it.

M31, or how I learned to stop worrying and love 700 billion stars

There are quite a few galaxies out there. Ironic as it may be, it’s far easier for us to get a good look at pretty much any one of them than it is for us to see our own. Being in the middle (but not at the center, that would be bad) of our fabulous Milky Way makes anything on the far side of our central bulge virtually impossible to examine. It’s like trying to understand the dimensions of a forest while surrounded by trees, there’s only so far you can look in most directions.

Pretty much all the “close” galaxies require at least binoculars or a small telescope to view, the distant ones require A LOT more. There’s one, however, that you can see with your naked eye, even in a somewhat light polluted area. I live within Boston city limits (though on the outskirts) and on a clear night, I can see it from my back yard, just by looking up. The one, the only, Andromeda Galaxy.

To the un-aided eye, it looks like a fuzzy patch, but an entire galaxy is what you’re looking at. Weighing in at about 700 billion solar masses (our sun=1 solar mass), this is a BIG galaxy. We can see it with relative ease because it’s 220,000 light years wide. The Milky Way is no chump, but this thing is a monster. It’s no Abell 2029 mind you, at least, not yet. There will come a day when it grows much larger, and we (residents of the Milky Way) are going to be a big part of it, and I don’t mean that figuratively.

In about 2.5 billion years it’ll be our new home, that is, once it has consumed the Milky Way. It’s headed this way, right now, at 300 kilometers per second. Fortunately for our immediate plans, its distance of 2.5 million light years will ensure it arrives fashionably late. By then our sun’s energy output will have gone up by 20% and will have long since evaporated our oceans and raised Earth’s mean surface temperature to something much like what Venus has now, thanks to all that evaporated ocean in our atmosphere. We’ll have either left for greener pastures or come up with some clever way to keep things cool long, long before any of this becomes an issue. If our descendants are still hanging around though, provided they still have heads with eyes, they’ll have one heck of a view when they look upat the night sky. Of course, we may evolve into eyeless mole people by then. There’s no doubt that we’ll be unrecognizably different that far out, should we endure. I’d say we probably have a 50/50 shot of avoiding moleification, but I digress.

Personally, I think this is a pretty bad ass thing to see, even for us 21st century humans that almost always have heads with eyes. Get some binoculars or a scope and it’s even more so! Either way, we have some clear nights coming and this will be high in the sky, just waiting for you. Currently, you’ll find it if you look straight up around midnight. How easy is that?

BUT WAIT! THERE’S MORE!!! If you act now (or at any point in your lifetime), you’ll also get to see M32 ABSOLUTELY FREE!

M32 is the dwarf galaxy that acts like a satellite around M31, which provides some additional influence on the larger galaxy’s star formation. The Milky Way has a couple of these as well, and some day, we’ll all be one big happy family. Well, all our stars will be part of the same greater object anyway. We’ll have to leave the happiness part to the mole people.

Shedding some light on the value of darkness

I’m kind of a tree-hugger. I honestly have a hard time understanding the mindset of those who think the earth is going to provide some kind of magic safety net for us and we can simply do as we please without consequence. Animals go extinct, the earth warms, weather gets crazy and while things change in measurable and predictable ways, the science and its warning is ignored by many. It sucks, but it’s my belief that in 20 years (or so), subjects like anthropogenic climate forcing (man-made global warming) will be part of common consciousness and pretty much universally accepted as true. We’re human and do human things. We wait to make changes until we have no other option. It will be costly, in every way, and those looking back in the centuries to come with think we’re fools for letting it happen at all. I’m inclined to agree.

With so many issues at hand, one that is near and dear to me (well, they all are, but this is still an astronomy blog) is the gradual loss of our night sky’s darkness. Fortunately, there is an amazing organization out to protect it. The International Dark-Sky Association has one goal: to preserve the enormously valuable natural resource that is our night sky. The thing I like most about them though is that they take an extremely pragmatic approach to their conservancy. They’re not going to picket the outdoor light fixture factory, they’re going to work with the EPA to make sure the light fixtures are built to meet standards that reduce light pollution. They also do a good job of showing various organizations and facets of government that if you’re creating light pollution, you’re also wasting taxpayer money.

This isn’t just an issue for astronomers, this is an issue for everyone. Have you ever seen a perfectly dark sky? It used to be so common, we took it for granted. I’m not here to preach, but is there anyone who truly thinks that losing our ability to see the wonders of the night sky is no big whoop? Let’s also remember that we’re not just looking at pinholes in a black curtain, this is our personal view into the depths of space. I’ll say it another way; when you look up at those stars and planets, you’re not looking at some projected image, you’re looking right into OUTER SPACE. I think we forget that, despite the glaring obviousness. It’s also completely free for anyone, on any clear night, should they care to look.

Even if you don’t care about being able to see the night sky, it should make you wonder why we spend YOUR money to light it up. We absolutely don’t have to sacrifice anything by not doing it and we get to save money too, which sounds like a no-brainer to me. What’s also a concern to every person that lives in an urban area is recent evidence that all this extra light may be VERY detrimental to your health.

I’m not saying that you should give all your money to the IDA or sign any petitions, much less write angry letters to congresspeople. Helping them and reducing light pollution PAYS YOU on its own. Take 90 seconds and visit their site, decide for yourself if this is something you think should be addressed.

But what about public safety? If we make everything darker, won’t the cities turn into the worst kinds of havens for villainy and scum? Nope! In fact, it’s EXACTLY THE OPPOSITE.

My point here is that preventing and reducing light pollution is a win/win/win situation. There is no downside, besides that we possibly have to do some pretty easy stuff. I think the huge dividends that miniscule effort pays are more than worth it. I can see no reason, at all, we have to let this get so bad we lose the sky before we do something about it. Does that make me a star-hugger too? If so, I think I can live with that.

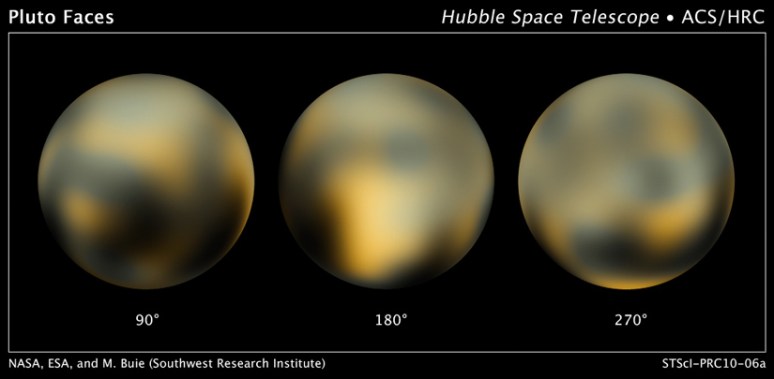

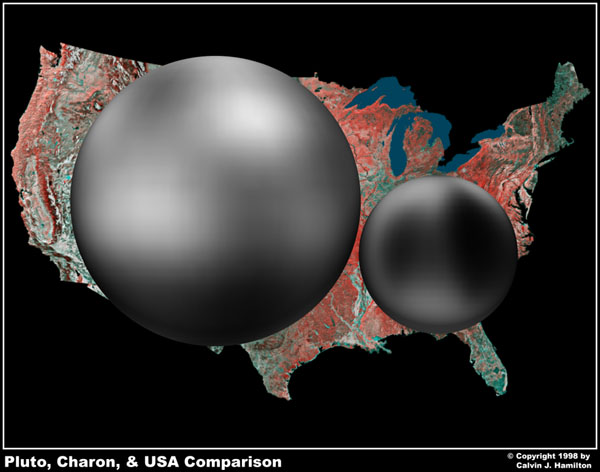

Let’s talk about Pluto

What is it that everyone loves so much about Pluto? It must be the mystery and controversy that seems to follow it wherever it goes. It’s not big, it seems there might be MANY more objects like it out there in the depths of the outer solar system and we truly don’t know all that much about it. We know its mass, we know its orbit and we know it has at least four small satellites. We also know Disney gave it a tribute with a dog character that actually acts like a dog, unlike Goofy, who is also a dog but acts like a person, which has always been confusing to me.

Animated characters aside, everyone knows Pluto is floating around out there and most are familiar with at least some of the controversy regarding its reclassification. Note that I didn’t call it a “demotion” from its previous designation as a planet. We call it a “dwarf planet” now, which I think feels a bit like some politically correct platitude we use in place of something that implies more diminished significance, even if something else might be more scientifically useful.

The issue, in essence (which is best understood if you read Mike Brown’s book), is that the word “planet” isn’t very descriptive. It comes from a Greek term ASTRA PLANETA, which literally means “wandering star”. If all you can do is look at a point of light that seems to change position relative to the other points of light in the night sky, then yeah, I guess that works, but today we need something a bit more exact. Mercury and Jupiter couldn’t be more different, once you get a good look at them, yet we use the same word to describe them both. Heck, Titan (Saturn’s largest moon) is even BIGGER than Mercury and has a real atmosphere, but it’s just a moon. See the problem?

To make things worse (for Pluto’s street cred anyway), we now are finding that there may be hundreds of Pluto-size objects in the Kuiper belt. The total number of smaller objects out there certainly number in the thousands. Many have HIGHLY elliptical orbits, even Pluto’s “crosses” Neptune’s (don’t worry, they’ll never collide), and some might even be hiding in plain sight.

The good news for Pluto, aside from the fact that it’s now clear people have some serious emotional attachments to it and are willing to insist that it gets respect, is that we’re going to get a close look at it. With a name like that of a celebrity rehab facility, New Horizons is just a bit more than half way there and is moving FAST. It launched the very year Pluto left the Planet Club (2006) and will arrive in 2015. To offer some perspective, Saturn is about 750 million miles away, yet the closest Pluto ever gets is about 2.6 BILLION miles away, the furthest is almost TWICE that. And you complain about your commute.

Plus, it’s downright hilarious to think about the engineering feat that goes into reaching a target as small as Pluto at such a distance, when it’s moving, nine years after you launch.

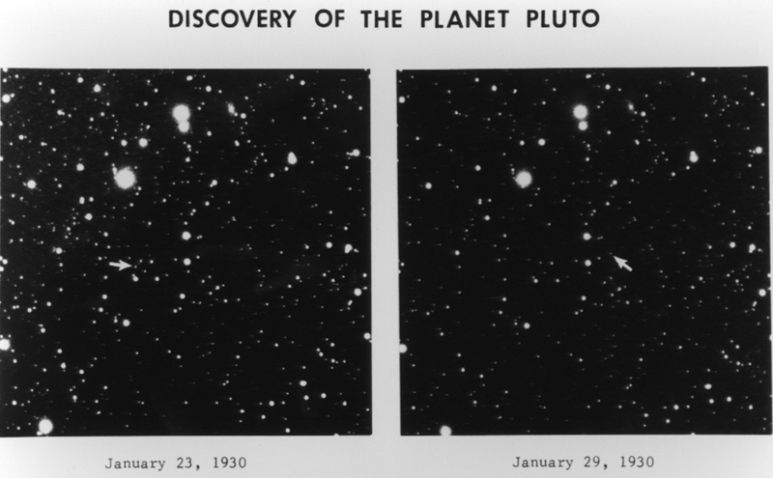

My guess is that once we get a close-up look at Pluto and company, we’re going to have a lot to talk about. There is no doubt that the discoveries made in this decade about these far out “Planetarially Challenged” worlds will teach us something about our solar system’s history. This is an exciting time for planetary science and spacecraft not withstanding, as our ability to observe our little corner of the galaxy improves, so does the frequency of our discoveries. Instead of manually trying to spot minute changes in a sea of little white dots on large photographic prints, we have digital imaging and software that can show us things we’d never find otherwise.

Normally I’d suggest trying to get out there and having a look at Pluto yourself, but it’s not at all an easy target. I’m not saying you shouldn’t try, but know what you’re getting yourself into. The fact it was discovered in 1930, at all, is astounding.

After some drama at the Lowell Observatory, a young Clyde Tombaugh was tasked with finding planet number nine. The funny thing is, the planet he was tasked with finding was not Pluto, but the mysterious “Planet X”. Neptune had been discovered not long before using careful observation of Uranus’ orbit and some math, but there was also a hint (or so they thought) that something else was messing with it as it slowly traveled around the sun. Pluto was not the scrappy troublemaker they had been searching for, but Tombaugh went ahead and found it anyway. It just happened to be the Kuiper belt object that was where Planet X should have been.

Through the 76 years of a nine planet solar system, Pluto has seemed to carry more pathos than any other celestial body. Even the way its name came about is touching. Instead of getting bent out of shape over messy designations, let’s just appreciate it and its Kuiper belt brethren for what they are: part of our solar family, history and culture.